The JNU Confrontation: A Microcosm of India’s Caste and Religious Divides

It is always a jolt when campus life turns into a flashpoint for the nation’s deepest fault lines. The recent unrest at Jawaharlal Nehru University (JNU) underscores how student politics, communal polarization, and institutional power dynamics intersect, often transforming campus rituals into battlegrounds for broader ideological struggles. Let’s dive into what went down, because this isn’t just a JNU story—it’s a mirror to India’s ongoing battles over caste, faith, and power.

The Spark: A GBM That Turned Into Chaos

Picture this: October 16, 2025. It’s a General Body Meeting (GBM) of the School of Social Sciences at JNU. Tensions simmer, and suddenly, a clash erupts between members of the Akhil Bharatiya Vidyarthi Parishad (ABVP), the BJP’s student wing, and left-leaning groups like the Students’ Federation of India (SFI) and All India Students’ Association (AISA).

The confrontation began when ABVP alleged that a left-wing councillor made derogatory remarks about students from Uttar Pradesh and Bihar, leading to physical scuffles that injured several participants, including the JNUSU President. Left groups countered that ABVP members initiated violence and hate speech, including casteist slurs against the JNUSU Vice President and Islamophobic abuse toward the General Secretary, all in the presence of Delhi Police who failed to intervene promptly.

It’s the kind of scene that leaves you shaking your head—fists flying, slurs echoing, and the supposed guardians of law just… watching.

The Aftermath: Protests, Detentions, and Uneven Justice

In the immediate wake, students didn’t sit idle. They marched to the Vasant Kunj police station to file a complaint against ABVP for the assault, but Delhi Police refused to register an FIR. Instead, on October 18, during a follow-up protest demanding accountability, police detained 28 students, including Kumar and seven women, and transported them to the Khaprahera police station.

This action allegedly violated guidelines prohibiting the overnight detention of women between 7 p.m. and 7 a.m., though such rules are often flouted in practice. The detainees were released next day morning amid student protests and mounting pressure. Notably, while an FIR was filed against six JNUSU leaders for allegedly manhandling police and breaking barricades during the protest, no formal charges have been lodged against ABVP members as of October 31, 2025.

This incident raises critical questions about institutional impartiality. Why was no action taken against those accused of instigating violence? According to left-leaning groups, the answer lies in a concerted effort by the JNU administration—influenced by the ruling party at both the Centre and in the Delhi state government—to hijack and derail the student union elections. The allegation is that by creating a climate of chaos and discrediting the electoral process, the administration aims to appoint representatives rather than allow a fair election. This, they argue, is a tactic employed by the ABVP, which fears electoral defeat based on prevailing campus issues, and thus uses violence to disrupt and discredit the opposition.

Punishing Muslim Assertion Versus Normalizing Majoritarian Aggression

I love Muhammad graffiti in JNU

Shifting gears to the heart of the bigotry on display—the right wing’s dread of electoral defeat at JNU manifests through Islamophobia, using divisive rituals to rally majoritarian votes by scapegoating Muslims. It relies heavily on polarizing rituals to consolidate a majoritarian vote bank by attacking Muslims and scapegoating them.

This was evident in the appearance of “I Love Muhammad” posters and graffiti on campus walls in October 2025 before the JNU student election. While the authorship remains officially unknown, the political consequence was clear: it polarized the student community. Such acts are seen by many as a deliberate provocation, likely orchestrated by forces aligned with the ABVP’s ideology, to create a communal fault line just before elections.

Now, zoom out to Uttar Pradesh where the pattern first echoed. The expression of “I Love Muhammad” used in Shab-e-Barat festival in 2025 led to arrests, dozens jailed on flimsy charges, and houses were bulldozed under BJP Chief Minister Yogi Adityanath’s administration for allegedly “disturbing communal harmony.” While processions with swords through Muslim neighborhoods during Ram Navmi (Rama’s Birthday) “Jai Shri Ram” chants, mosque attacks, and lynching by cow vigilantism often go unpunished—sometimes even celebrated as assertions of Hindu pride—Muslim expressions of faith are swiftly criminalized as threats to harmony.

The narrative, therefore, is engineered: Muslim assertion “disturbs harmony,” while majoritarian aggression is often normalized.

These recent events, like the “I Love Muhammad” posters and Ravana effigy burnings with activists’ faces, are being used to divide students and influence the upcoming JNU Student Union (JNUSU) elections. This is not a one-off case of anti-Muslim hate on campus. JNU has a history of such issues, especially under the current government.

The Disappearance of Najeeb Ahmed and the Silencing of Muslim Voices

Take the case of Najeeb Ahmed, a Muslim student who went missing on October 15, 2016, after an alleged assault by ABVP members outside his hostel. His disappearance shocked the entire JNU community and became a symbol of institutional apathy. For nearly a decade, his family—especially his mother, Fatima Nafees—has lived through relentless anguish, protests, and unanswered questions in their search for justice. As of October 2025, nine years later, the police have neither found his body nor solved the case. The CBI officially closed the investigation in July 2025, but Najeeb’s family continues to fight in court to have it reopened.

This enduring pain has only deepened the sense of fear among Muslim youth on campus. Prominent activists like Umar Khalid and Sharjeel Imam have been jailed since 2020 under the Unlawful Activities (Prevention) Act (UAPA)—a law often criticized for its sweeping and repressive reach.

Umar Khalid is accused by Delhi Police of “conspiring” to incite the communal violence that broke out in northeast Delhi in February 2020. According to the police, the anti-CAA protests were allegedly used as a “cover” for a larger conspiracy to provoke the riots—an allegation widely contested by rights groups and academics.

Sharjeel Imam’s UAPA charges stem from a speech he delivered in January 2020 at Aligarh Muslim University and later at Jamia Millia Islamia, where he called for a “chakka jam” (road blockade) as a non-violent form of protest against the Citizenship Amendment Act (CAA) and the proposed National Register of Citizens (NRC).

Both have been waiting for over five years for a fair trial, with bail pleas repeatedly denied. Their prolonged incarceration sends a chilling message—if Muslim students speak up for their rights or dare to criticize the government, prison awaits.

Heartbreaking, isn’t it? It’s a stark reminder of how dissent, when voiced by certain identities, doesn’t just get ignored—it gets criminalized.

Festivals Weaponized: Portraying Muslims as Evil

This hate builds up more during festivals. In the 2025 Dussehra celebrations at JNU, ABVP pasted photos of Umar Khalid and Sharjeel Imam on Ravana’s effigy heads before burning it. They called it a win of good over evil. But to many, it labels thinking, speaking Muslims as “evil” and shows their fate.

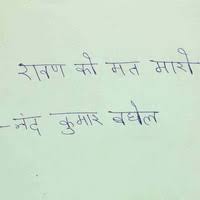

Ravan Ko Mat Maro, Book cover

At this point, it’s worth noting Nand Kumar Baghel’s 2000 book, Brahman Kumar, Ravan Ko Mat Maro (Don’t Kill Ravana, Brahmin Son). Baghel, a social activist and father of former Chhattisgarh CM Bhupesh Baghel, wrote it as a call to upper-caste Hindus. He said Ravana’s “demon” tag hides caste bias and hurts Dalits, Adivasis (tribal people), and Buddhists. He pushed for talks between groups and wanted Dussehra rituals to celebrate shared culture, not burn symbols of the oppressed.

While most Hindus burn Ravana’s effigy on Dussehra to show good beats evil, some tribal and local groups see him differently. They view Ravana as an ancestor, wise scholar, or Shiva fan. In places like Bisrakh village (Uttar Pradesh), they worship his photo and fast instead of burning. Gond tribes in Madhya Pradesh and Chhattisgarh call him a hero and do puja. Rarely, some invert the story—seeing Ram as an outsider—and burn his effigy in protests for tribal pride.

Mahishasura Day at JNU: A Clash Over Ancestral Heroes

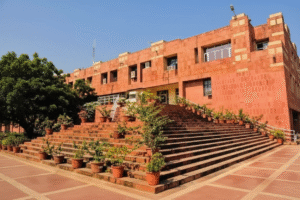

JNU, Delhi

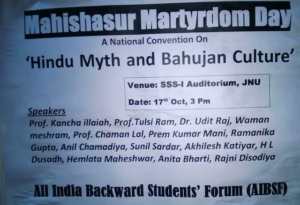

Something similar happened with Mahishasura Day at JNU in 2011. Tribal groups like Gond and Munda see Mahishasura (the buffalo demon killed by Goddess Durga) as their hero and protector, not a villain. They say Durga tricked and killed him to favor upper-caste gods like Indra. The All India Backward Students’ Forum (AIBSF) held an event to honor him and fight for tribal pride. But the JNU administration resisted: They sent show-cause notices to the AIBSF president, suspended two students for “offensive” posters, and even cancelled the event with police help after clashes with ABVP.

The real story at JNU is not just anti-Muslim bias—it’s a system rigged to uphold upper-caste dominance, systematically erasing indigenous gods, cultures, voices and existence. Tragically, many from oppressed castes unwittingly join in, worshiping figures like Durga as their protector while ignoring how her myths celebrate the slaughter of their own ancestors—like Mahishasura, revered by Adivasi groups such as Gonds and Mundas as a tribal hero felled by upper-caste deities. Across castes, Durga Puja draws huge crowds, but for Dalits and tribals, it’s a blind spot: They revel in the festival, unknowingly honoring the very symbols that stripped their dignity and pride.

Fractured Lines: Caste, Religion, and the Erosion of Resistance

This divide fractures the campus along caste and religious lines, with biases festering long before BJP’s 2014 rise. Even in “secular” left circles—often led by upper castes—it hid behind progressive language, sidelining Dalit pain. Ambedkarite outfits like BAPSA have long called out this “pseudo-left” for tokenism, noting how Brahmin presidents dominated 20 of 39 JNUSU elections pre-2014.

Criticizing caste privilege or demanding Dalit rights not only unsettles upper-caste leftists but also undermines the RSS’s imagined “Hindu unity.” Hence, Muslims become the easier targets—cast as cultural outsiders whose persecution doesn’t fracture caste solidarity within Hindutva’s project.

Though contradictions within JNU persist, the university and its ecosystem have long stood as rare spaces where oppressed voices could speak without fear—a site of intellectual freedom and resistance that consistently unsettled both upper-caste elites and right-wing forces. For decades, JNU embodied the idea that education could empower the marginalized, question entrenched hierarchies, and nurture fearless critique.

Take, for instance, the SC/ST (Prevention of Atrocities) Act, 1989. Its very mention once unsettled many upper-caste faculty and students, evoking discomfort—even fear—because it represented the legal and moral assertion of equality by those long denied it. JNU was precisely that kind of space: one where the most oppressed found the courage to speak, think, and express freely; to resist and correct systems of dominance that existed both inside and outside academia.

But that defining freedom is now fading. With the rise and consolidation of right-wing dominance, the campus’s plural and critical culture is being systematically undermined. What we’re witnessing is not just a shift in student politics or an ideological contest—it’s something far deeper.

At stake is the very soul of the university: the belief that educational institutions can still be spaces of equality, critique, and resistance in an increasingly majoritarian India.